Table of Contents

Scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) are down after the pandemic. Surprise!

Four big thoughts on all of this…

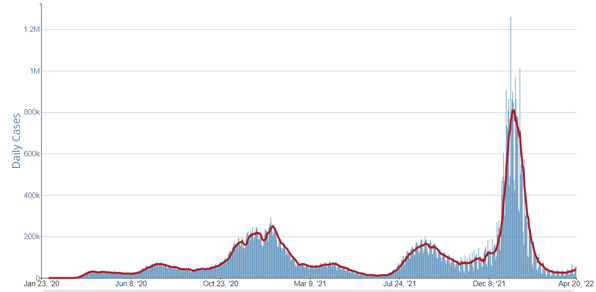

1. Below is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) graph of daily COVID cases in the U.S. Note the huge spike in January 2022 due to the Omicron variant. Also note that the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) chose to administer the NAEP tests in March 2022, during the downswing of that huge spike in cases and after two years of COVID trauma (six weeks later America hit the 1 million dead mark). How many kids, families, and educators were ill, recovering from being ill, or still traumatized from loved ones’ deaths, illnesses, or long recoveries? We’ll never know.

2. Always remember that the labels for NAEP ‘proficiency’ levels are confusing. Journalists (and others) are failing us when they don’t report out what NAEP levels mean. For instance, the New York Times reported this graph today from NCES:

“Appalling,” right?! That’s what the U.S. Secretary of Education, Miguel Cardona, said about these results. Just look at those low numbers in blue!

“Appalling,” right?! That’s what the U.S. Secretary of Education, Miguel Cardona, said about these results. Just look at those low numbers in blue!

BUT… ‘Proficient’ on NAEP doesn’t mean what most folks assume it does. NAEP itself says that ‘Proficient’ does not mean ‘at grade level.’ Instead, the label Proficient is more aspirational. Indeed, it’s so aspirational that most states are not trying to reach that level with their annual assessments. See the map below from NCES (or make your own), which shows that most states are trying for their children to achieve NAEP’s Basic level, not Proficient:

Once again, in the words of Tom Loveless, former director of the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution, “Proficient on NAEP does not mean grade level performance. It’s significantly above that.” So essentially the New York Times and others are reporting that “only one-fourth of 8th graders performed significantly above grade level in math.” Does that result surprise anyone?

Loveless noted in 2016 that:

Equating NAEP proficiency with grade level is bogus. Indeed, the validity of the achievement levels themselves is questionable. They immediately came under fire in reviews by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Academy of Education. The National Academy of Sciences report was particularly scathing, labeling NAEP’s achievement levels as “fundamentally flawed.”

Loveless also stated:

The National Center for Education Statistics warns that federal law requires that NAEP achievement levels be used on a trial basis until the Commissioner of Education Statistics determines that the achievement levels are “reasonable, valid, and informative to the public.” As the NCES website states, “So far, no Commissioner has made such a determination, and the achievement levels remain in a trial status. The achievement levels should continue to be interpreted and used with caution.”

Confounding NAEP proficient with grade-level is uninformed. Designating NAEP proficient as the achievement benchmark for accountability systems is certainly not cautious use. If high school students are required to meet NAEP proficient to graduate from high school, large numbers will fail. If middle and elementary school students are forced to repeat grades because they fall short of a standard anchored to NAEP proficient, vast numbers will repeat grades. [emphasis added]

In 2009, Gerald Bracey, one of our nation’s foremost experts on educational assessment, stated:

In its prescriptive aspect, the NAEP reports the percentage of students reaching various achievement levels—Basic, Proficient, and Advanced. The achievement levels have been roundly criticized by many, including the U.S. Government Accounting Office (1993), the National Academy of Sciences (Pellegrino, Jones, & Mitchell, 1999); and the National Academy of Education (Shepard, 1993). These critiques point out that the methods for constructing the levels are flawed, that the levels demand unreasonably high performance, and that they yield results that are not corroborated by other measures.

In spite of the criticisms, the U.S. Department of Education permitted the flawed levels to be used until something better was developed. Unfortunately, no one has ever worked on developing anything better—perhaps because the apparently low student performance indicated by the small percentage of test-takers reaching Proficient has proven too politically useful to school critics.

For instance, education reformers and politicians have lamented that only about one-third of 8th graders read at the Proficient level. On the surface, this does seem awful. Yet, if students in other nations took the NAEP, only about one-third of them would also score Proficient—even in the nations scoring highest on international reading comparisons (Rothstein, Jacobsen, & Wilder, 2006).

The NAEP benchmarks might be more convincing if most students elsewhere could handily meet them. But that’s a hard case to make, judging by a 2007 analysis from Gary Phillips, former acting commissioner of NCES. Phillips set out to map NAEP benchmarks onto international assessments in science and mathematics.

Only Taipei and Singapore have a significantly higher percentage of “proficient” students in eighth grade science (by the NAEP benchmark) than the United States. In math, the average performance of eighth-grade students could be classified as “proficient” in [only] six jurisdictions: Singapore, Korea, Taipei, Hong Kong, Japan, and Flemish Belgium. It seems that when average results by jurisdiction place typical students at the NAEP proficient level, the jurisdictions involved are typically wealthy.

We can argue whether the correct benchmark is Basic or we should be striving for Proficient, and we all can agree that more kids need more support to reach desired academic benchmarks. But let’s don’t pretend that ‘Proficient’ on NAEP aligns with most people’s common understandings of that term. We should be especially wary of those educational ‘reformers’ who use the NAEP Proficient benchmark to cudgel schools and educators.

3. Lest we think that these NAEP results are new and surprising, it should be noted that scores on NAEP already were stagnant. Achievement gaps already were widening. After nearly two decades of the No Child Left Behind Act and standards-based, testing-oriented educational reform – and almost 40 years after the A Nation at Risk report – the 2018 and 2019 NAEP results showed that the bifurcation of American student performance remained “stubbornly wide.” We continue to do the same things while expecting different results, instead of fundamentally rethinking how we do school.

4. The pundits already are chiming in on the 2022 NAEP results. They’re blaming overly-cautious superintendents and school boards, “woke” educators, teacher unions, parents, online learning, video games, social media, screen addiction, “kids these days who don’t want to work,” state governors, and anything else they can point a finger at. As I said yesterday, it’s fascinating how many people were prescient and omniscient during unprecedented times, when extremely challenging decisions needed to be made with little historical guidance, in an environment of conflicting opinions about what was right. Despite the massive swirl of disagreement about what should have occurred during the pandemic, many folks are righteously certain that they have the correct answer and everyone else is wrong. The lack of grace, understanding, and humility is staggering.

Also, look again at the graph above. One way for journalists, commentators, and policymakers to frame those results is to call them ‘appalling.’ Another way is to say:

Scores are down but, even during a deadly global pandemic that shut down schools and traumatized families, the math and reading achievement of about two-thirds of our students stayed at grade level or above. How do we help the rest?

Always consider how an issue is framed and whose interests it serves to frame it that way (and why).

We can whirl ourselves into a tizzy of righteous finger-pointing, which is what many folks will do because it serves their agenda to do so. Or we can

I think that it’s unlikely that many states, schools, and communities will actually do this because of the fragility and brittleness of our school structures. But I’m pretty sure that the path forward is not simply doubling down on more math, reading, and testing, and it sure isn’t uncritically accepting NAEP results.

Your thoughts?